The Optional Vaccines Your Dog May Really Need

Core vaccines (see Chapter 3) should be given to any dog, whatever the situation.

On the opposite, non-core vaccines are optional vaccines that should only be administered upon consideration of the risks your dog runs, and which depend on:

- the pathogenic germs known to be present in your region

- your dog's lifestyle

- your dog's health condition

- your dog's age

The "Non-core vaccines" concept was developed by a board of veterinary experts from the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. The goal of the Vaccination Guidelines Group (VGG) was to help veterinary practitioners design vaccination schedules that provide optimal protection to dog patients while reducing the vaccine load to a minimum.

They are non-live vaccines (inactivated) which induce a shorter duration of immunity than core vaccines. They require an annual booster.

Non-core vaccines protect against:

- Respiratory diseases

- Lyme diseases

- Leptospirosis

Vaccines against infectious respiratory diseases

Kennel Cough is the most commonly used name for dog infectious respiratory diseases. But you may read other names: infectious tracheobronchitis (ITB), canine infectious respiratory disease (CIRD), or even canine infectious respiratory disease complex (CIRDC).

Infectious respiratory diseases are generally initiated by viruses:

- Canine parainfluenza virus (CPiV)

- Canine adenovirus-2 (CAV-2)

- Canine influenza virus (CIV)

- Canine distemper virus (CDV)

Or by a bacterium: Bordetella bronchiseptica.

Other pathogens can be found in dogs with Kennel Cough. They are considered as secondary or opportunistic pathogens, meaning that they should not cause the disease, but are present and may worsen the symptoms. They are:

- Viruses: canine respiratory coronavirus (CRCoV) and canine pneumovirus (CnPnV).

- Bacteria: Streptococcus zooepidemicus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella and Mycoplasma

Often, a single pathogen doesn't act alone and a combination of viruses and bacteria are involved in the most severe forms of respiratory diseases.

A study on dogs with canine infectious respiratory disease in Germany illustrates the situation. However, the pathogens may vary greatly from one region to another.

Some respiratory pathogens

Canine Parainfluenza Virus (CPIV)

CPIV is a common and very contagious virus. It settles in the nose, pharynx, larynx, trachea and bronchi where it replicates. It attacks the mucosa and bares very rapidly large parts of the epithelium by destroying the cilia.

CPIV is responsible for the well-known goose honk cough. The infection resolves spontaneously within 6-14 days except in the cases of co-infection with another virus or with Bordetella bronchiseptica.

Bordetella bronchiseptica

Bordetella bronchiseptica is the most virulent bacterium involved in canine respiratory diseases.

Bordetella resides in the respiratory tract of healthy dogs. For some still unknown reasons (weakened immune system, viral infection ?), the bacterium can "wake up" and start colonizing respiratory tissues.

Bordetella is virulent in many ways. It paralyzes the ciliary movements that help clear away foreign bodies from the mucosa (see Chapter 1: the first line of defense of the immune system). It then binds to the respiratory epithelium thanks to filamentous proteins (hemagglutinins, fimbriae).

Bordetella releases many toxins. Some of them induce respiratory epithelium necrosis while others help the bacterium elude the host's immune defense.

Canine Influenza Virus (CIV)

The route of contamination is airborne or through contact with contaminated objects.

The virus incubates for 2 to 4 days. Then, it colonizes the nasal cavity, the trachea and the conducting airways inducing an inflammation that may cause a rhinitis, a tracheitis, a bronchitis or a bronchiolitis. It also opens doors to bacterial superinfections.

The symptoms are coughing and nasal discharge. The disease typically lasts for 10-20 days. Over that period of time the dog keeps on shedding viruses and being contagious. It should be kept away from other dogs (and cats).

Canine Adenovirus type 2 (CAV-2)

CAV-2 is part of the core vaccination recommendations (see Chapter 3).

CAV-2 enters the body through the nose or mouth. It replicates in the upper respiratory tract and in non-ciliated bronchiolar epithelial cells.

The infection peaks at 3-6 days after infection and recedes within 9 days. It causes inflammation of the airways.

Without co-infective pathogens the symptoms in adult dogs are mild (cough, expectoration of mucus), although damage in the lungs may be extensive.

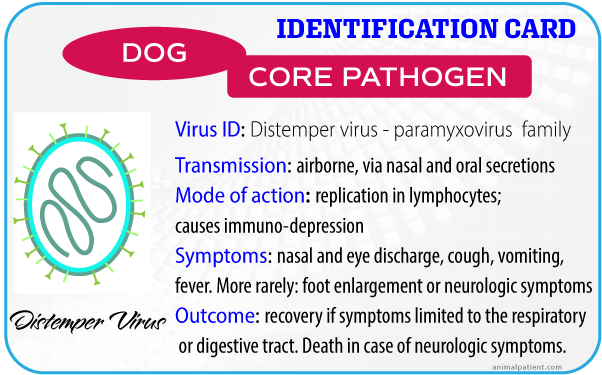

Canine Distemper Virus

Canine Distemper Virus is part of the core vaccination recommendations (see Chapter 3).

The virus is usually airborne, but can also contaminate dog food. It first replicates in some white cells of the immune system and then colonizes many other organs.

In addition to the signs of infectious respiratory disease (nasal and eye discharge, coughing) infected dogs may display digestive or neurologic symptoms.

Symptoms

As always in infectious diseases, the symptoms and outcomes are more severe for young puppies than for adult dogs.

In adult dogs the symptoms of a viral infection range from intense episodes of coughing and expectoration lasting for 1 to 3 weeks to hardly any symptoms at all.

Bacterial superinfections add other types of symptoms: fever, dyspnea (irregular breathing) purulent nasal and ocular discharge and loss of appetite.

The infection may develop into a life-threatening pneumonia, especially in puppies.

Treatment and prevention

Many antibiotics from different classes can be prescribed against the bacteria involved in respiratory diseases.

They complement supportive therapies, which treat symptoms but not the cause of the disease: antitussives, glucocorticoid anti-inflammatories, and/or bronchodilators.

Vaccination is the only protection against viruses. Your vet may advise you to complement the core vaccination program with vaccines against respiratory pathogens if he thinks your dog is particularly exposed.

Canine adenovirus-2 (CAV-2) and canine distemper virus (CDV) are already part of the core vaccination program that should be administered to any dog.

Vaccines against the bacterium Bordetella bronchiseptica, canine parainfluenza virus, and canine influenza virus are optional, non-core vaccines. But, because these pathogens are very contagious, they are recommended for dogs which can get in contact with other dogs in kennels, in shelters or in co-housed environments.

Non-core respiratory vaccines are NOT INDICATED if your dog is NOT EXPOSED to other dogs.

Example of a vaccination schedule for a dog exposed to respiratory pathogens

| Years of age | Core vaccines | Non-core vaccines |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | DHP unless it was given at 26 weeks in the puppy schedule | CPi, Bb |

| 2 | CPi, Bb | |

| 3 | CPi, Bb | |

| 4 | DHP or serology | CPi, Bb |

| 5 | CPi, Bb | |

| 6 | CPi, Bb | |

| 7 | DHP or serology | CPi, Bb |

| 8 | CPi, Bb | |

| 9 | CPi, Bb | |

| 10 | DHP or serology | CPi, Bb |

Bb: Bordetella bronchiseptica - Cpi: Canine parainfluenza virus - DHP: Canine distemper virus, canine adenovirus, canine parvovirus type 2

Main references

Borrelia burgdorferi

Borrelia burgdorferi is a spirochete bacterium that causes Lyme borreliosis also known as Lyme disease (or Lyme arthritis in human medicine). It is transmitted exclusively by ticks of the genus Ixodes.

Spirochetes are long and slender bacteria with a characteristic helical or corkscrew shape. They are mobile in a liquid environment thanks to their flagella that makes the cell undulate.

As a consequence, and unlike other bacteria, spirochetes do not rely only on host's body fluid movements (blood and lymph) to move. They can swim. It makes them very invasive because they can get deeper into tissues and colonize many organs in their host.

Transmission

Borrelia burgdorferi is transmitted by ticks of the genus Ixodes: mainly Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus in North America or Ixodes ricinus in Europe. In some very rare cases, it can also be transmitted in utero or through the urine or the mother's milk.

Ticks have three development stages: larval, nymphal and adult. At each stage they have to find a different host on which they attach and feed with blood for a period of 3 to 5 days. The blood that ticks take from their host dilates their abdomen so much that it increases their total size up to 3 times.

Ticks need this blood meal to reach their next development stage. Once fed, they detach from their host, fall on the ground and molt to the next stage (larva or adult) or lay eggs (when they fed on their host as adults).

A tick gets infected by the bacterium Borrelia in its earlier stage as a larva or even as a nymph when feeding on an infested mammal, usually a rodent. Borrelia then migrates to the gut of the tick where it replicates and resides, waiting for the next host and the next blood meal.

On a new host, a tick walks around for a suitable place to feed on. It inserts its capitulum deeply in the host's derma. It sucks blood for 3 to 5 days. In many occasions, it regurgitates saliva back into its host's blood.

Tick's saliva contains different types of substances that help:

- Cement the capitulum to the host skin

- Inhibit blood coagulation and platelet aggregation

- Vasodilate capillary blood vessels

- Prevent itching and pain

In addition to Borrelia, ticks' saliva may also contain other pathogens got from a meal on a previous host: tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV - other name for Powassan virus), Babesia, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia bacteria. They respectively may cause encephalitis, babesiosis, anaplasmosis, and ehrlichiosis.

These pathogens are always transmitted by the tick to the new host during the regurgitation episodes.

It is widely recognized that the transmission of Borrelia in a new host, let say a dog, takes place 24-48 hours after the beginning of the feeding process. However, a very recent study shows that it could be much quicker and occur only a few hours after the beginning of the meal (unpublished study - to be confirmed).

To get infected your dog needs to live in places where:

- Ixodes ticks live

- and where there are rodents infected with Borrelia burgdorferi

As the mode of transmission is the same for dogs as for humans, the risk to get Lyme disease is nearly the same for you or your family as it is for your dog. You can find the US Lyme disease human epidemiology map here

You'll notice that living in the North Eastern part of the US is more risky.

There is no such map for Europe. Instead, you may track the presence of the vector tick, Ixodes ricinus in Europe

Symptoms

In human patients

Lyme disease is a major public health concern. In the US, it is the second infectious disease (300 000 cases) just after AIDS. In Germany, estimates show that 1 million people could be infected!!

The first human symptom consists of a characteristic erythema migrans that develops over a few days after the tick has bitten. It is a reddish round skin rash around the tick's bite that progressively enlarges before it disappears.

The erythema migrans correlates with the replication phase of the bacterium within the skin, at the bite site. It may be associated with fever or nasal discharge.

The infection should be treated early, during this phase. Because the most serious effects come well after, sometimes years after, in the form of chronic systemic disorders affecting the heart, the brain, the joints (read more at The Center for Disease Control and Prevention - Lyme disease).

In dogs

In dogs, it is not that bad. Only 5% of dogs infected with Borrelia Burgdorferi develop symptoms: transient fever, anorexia, and arthritis (Littman et al. 2006). They affect mainly puppies and resolve spontaneously within a few days.

Nevertheless, the infection deserves some attention on the long run. Dogs tested positive to Borrelia antibodies tend to develop a certain type of renal disease: a protein-losing nephropathy.

In addition, co-infection with other pathogenic micro-organisms (bacteria, parasites) usually transmitted by Ixodes ticks may cause some sort of lameness or arthrosis.

Diagnosis and treatment

Blood tests measure the presence of antibodies specific to Borrelia.

A positive result indicates that the dog was contaminated with the bacterium, recently or in the past, or that it was vaccinated against Borrelia.

If your dog is seropositive AND displays the symptoms that are consistent with Lyme disease, your vet may prescribe an antibiotic treatment. The standard treatment is doxycycline twice a day for one month. Without symptoms no treatment is necessary.

If your dog is seropositive, your vet should consider the possibility of a renal disease and of a co-infection by a pathogen transmitted by ticks of the genus Ixodes.

Prevention

The first question you should ask yourself is whether you live in a risky place: is there in your area Ixodes ticks that carry Borrelia bacteria?

To answer this question you should either ask local medical professionals and/or look at epidemiologic maps (see above).

If so, it means that your four-legged friend is exposed. But more importantly, that you and your family are also at risk!!

Borreliosis is a much more severe disease in humans than in dogs. And ticks can bite you or your dog just the same way.

Priority #1: protect yourself and your family whenever you are going in a possibly contaminated area (typically, tick-infested woods):

- Wear long trousers and shirts with sleeves.

- Prefer bright clothings, because it's easier to spot ticks on them

- Use skin-applied repellents

- After your walk, have a shower and use a washcloth

- Examine your body (you may ask for help). Pay special attention to hot and wet areas: the armpits and the groins. Don't forget that before they feed, tick are very small, especially the larvae. If you find one, detach it with a tick removal forceps. Never use chemicals because they may make the tick regurgitate. Monitor the place where the tick bit for an erythema migrans, as a sign you've been contaminated with Borrelia

Priority #2: protect your pets against ticks.

Because ticks carry other diseases, it is more important to protect dogs against ticks than to vaccinate them against borreliosis.

There are some ticks repellents/killers on the market that prevent tick bites (at least part of them). Ask your vet about them.

Priority #3: consider vaccinating your dog

There are a few vaccines available. 2 injections, 2 to 4 weeks apart, should be administered to young puppies, and then booster should be injected once a year.

There are some adverse events in less than 2% of the cases. They involve an unwanted immune reaction. This is the same type of adverse reactions that caused the human vaccines to be discontinued.

Should you vaccinate your dog against Borrelia burgdorferi?

Vaccination in non-endemic regions is not necessary.

In endemic areas, the issue is still controversial. Some vets vaccinate, most experts don't (ACVIM Small Animal Consensus Statement on Lyme Disease in Dogs). Opponents to vaccination argue that the disease in dogs is mild and can be cured easily with a proper antibiotic treatment. They also point out that vaccination against Borrelia doesn't prevent the transmission of the other tick-borne pathogens (namely, TBEV virus, Babesia, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia).

Main references

Leptospira interrogans

Leptospirosis is also a very important public health issue. It is a zoonosis: it can be transmitted directly from dogs to humans.

The bacterium Leptospira interrogans is widely spread all over the world. 5% of infected people die (see Global Burden of Leptospirosis publication on the topic). Children are especially vulnerable, and the disease is more frequent in hot and developing countries.

Leptospira interrogans is a spirochete bacterium. As every other spirochete, it is long and thin and has a flagellum that makes it very mobile and very invasive. It can infect any organ.

There are different subtypes of the bacterium. They are called serovars. It's important you are aware of these types because they have some practical implications on the serological diagnosis of the disease and on the vaccination strategy.

The serovars that are found in dogs are: Canicola, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Grippotyphosa, Pomona, and Bratislava

Transmission

Leptospira bacteria are shed in the urine of infected mammals. They survive longer in humid and warm environments.

They contaminate the soil or the water a new mammal host may drink. They can also enter a new host's body through a wound or any type of mucosa: mouth, nose, eye conjunctiva.

Something you need to keep in mind with Leptospira is that there are 2 types of hosts that can be infected:

- reservoir (or maintenance) hosts in which the bacterium multiplies actively, but cause mild or no symptoms. These hosts shed large quantities of bacteria in their environment. They may also develop some chronic diseases, and especially a chronic kidney disease

- incidental hosts which develop the acute symptoms of the disease

This distinction between accidental and reservoir hosts change according to the serovar.

Common Maintenance Hosts of the Pathogenic Leptospires Associated with Disease in Domestic Animals in the USA and Canada

| Leptospiral Serovar | Maintenance Hosts |

| Canicola | Dogs |

| Pomona | Pigs, cattle, opossums, skunks |

| Grippotyphosa | Raccoons, muskrats, skunks, voles |

| Hardjo | Cattle |

| Icterohaemorrhagiae | Rats |

| Bratislava | Pigs, mice (?), horses (?) |

Source: merckvetmanual.com/generalized-conditions/leptospirosis

Typically, rodents serve as a reservoir for the bacterium. They can pass it to dogs or directly to humans. Contamination may also come from large animals: horses, bovines or swine.

Humans may get infected. They always are incidental hosts.

Professionals such as veterinarians, farmers, breeders, pet shop workers that work or live in proximity to animals are more at risk to be infected. They should protect themselves (wear gloves, waders...) and may get vaccinated.

Disease mechanism

Leptospira first incubates for 4 to 20 days in the tissues close to its entry site.

It then migrates to different organs, mainly the kidneys, the liver, the lungs or stays in the blood. It is the acute stage of the disease.

If the infected animal is an incidental host, the bacteria are finally eliminated by the immune system. If it is a reservoir host, the infection becomes chronic, Leptospira bacteria remain and replicate within the kidney and keep on shedding in the urine.

Symptoms

In dogs, as for the other mammals, they can vary from mild to very severe and may lead to death.

Leptospira attacks primarily the kidneys, the liver, the lungs and the blood. Note that several organs can be affected at the same time.

Kidney

Acute kidney insufficiency (= acute renal failure) is the main symptom in dogs infected by Leptospira. The kidneys lose their ability to produce urine. As the blood can't be filtered anymore, toxins accumulate. Excess of water in the body can't be eliminated and causes overhydration. It is characterized by the rapid onset of vomiting, diarrhea and anorexia (get more information here).

This is a medical emergency. It is reversible if treated on time by fluid and supportive therapy. However this episode of acute kidney failure may trigger the onset of an irreversible, slowly progressing chronic kidney disease. In practice, if your dog was infected by Leptospira, you should ask your vet to monitor regularly its renal function.

Liver

Leptospira causes liver cells destruction. It is generally considered that the disease develops once the liver has lost 70% of its initial mass. Symptoms are not specific to the disease and many are similar to those of kidney disease: anorexia, vomiting, abdominal pain, and/or diarrhea which make the diagnosis difficult. In addition the dog may suffer from excessive thirst and urination.

In the more severe cases, the dog may develop icterus (jaundice) and/or hepatomegaly (liver enlargement) accompanied by abdomen edema.

The diagnosis is confirmed by blood tests and imaging.

Lungs

Severely affected dogs may develop a pulmonary hemorrhage which is the most frequent human manifestation of the disease. It is not common in dogs though. More frequently dogs only exhibit coughing and irregular breathing (dyspnea).

Hemorrhagic

Manifestations are diverse. They may be small red spots of blood just under the skin (petechial hemorrhage), nosebleed (epistaxis), bleeding of the intestinal tract causing black tarry stools (melena) and/or vomiting of blood (hematemesis).

The table below shows the repartition of the symptoms in about 250 dogs with leptospirosis examined at the Veterinary University of Bern (Switzerland). A single dog may have different manifestations of the infection at the same time.

Obviously, in this study almost all dogs have renal disorders.

| Organ Involvement | N affected/N total | % affected |

|---|---|---|

| Renal | 255/256 | 99.6% |

| Pulmonary | 194/253 | 76.7% |

| Hepatic | 66/254 | 26.0% |

| Hemorrhagic | 38/209 | 18.2% |

Diagnosis and treatment

As leptospirosis symptoms are not specific to the disease, your vet can't rely only on them to make a diagnosis. Complementary tests and imaging are necessary.

The first step is to try to determine what organs are affected. To do that, your vet will first perform blood and urine tests.

Blood tests

- Abnormal values in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and/or hyperbilirubinemia reveal hepatic disorders

- Changes in urea and creatinine signal kidney disease

- Abnormal blood phosphate, potassium, sodium or chlorine suggest leptospirosis.

Urine tests

The presence of protein, glucose or blood signals renal failure.

Imaging

Radiography and/or echography are usually performed to get a better view of the damages to the lungs, kidneys or liver with their possible consequences such as edemas.

When a leptospirosis is suspected, there is still a need for confirmation. 2 types of test can be used:

- MAT (microscopic agglutination test) test detects anti-Leptospira antibodies. It has some limitations and is subject to false positive or false negative results. If the dog was previously vaccinated against Leptospirosis, the veterinarian will have to perform the test twice to make the difference between infectious and vaccinal antibodies (in case it is the disease, the quantity of antibodies increases after the first test).

- PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test looks for Leptospira DNA. It should be performed on both urine and blood. A positive result on blood with clinical signs indicates the dog is infected. A positive result on urine shows that it is shedding bacteria in the urine and therefore contaminates the environment. There may be some false negative though.

Diagnosing leptospirosis in dogs is far from easy. But it is necessary. This is a matter of public health. You can't afford the risk that your dog contaminates your household or your neighborhood.

Fortunately treating leptospirosis is easy. A 14-day treatment with doxycycline, ampicillin, penicillin or amoxicillin is usually recommended.

However, you vet may also need to take care of hepatic, renal or respiratory disorders, on the long term. But this is another story...

Prevention

Vaccination against Leptospira is not considered as core by the board of WSAVA experts. This is because some indoor dogs kept away from wildlife, environmental water sources or any other source of contamination may not need it.

However, this is not a common situation and it is highly recommended to vaccinate all other dogs. Leptospirosis is a severe disease that is not easy to diagnose and that is transmissible to humans.

Newer, quadrivalent vaccines are recommended. They offer protection against Canicola, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Grippotyphosa and Bratislava serovars.

Main references

Not recommended vaccines

Some vaccines are not recommended by the WSAVA's Vaccines Guidelines Group.

Canine coronavirus vaccines

This recommendation of the VGG is based on 2 reasons:

- there is insufficient evidence that coronavirus vaccines are protective: it is unclear whether available vaccines protect against the most virulent variants of the virus

- enteric coronavirus is not a significant pathogen in dogs

Canine adenovirus type 1 vaccines

Canine adenovirus type 1 vaccines protect against canine adenoviruses type 1 and type 2. The same is true for canine adenovirus type 2 vaccines that protect against both viruses.

Against adenoviruses, you would rather administer live attenuated vaccines that are more effective and trigger both humoral and cellular immunity.

The issue here is that live vaccines may revert back to their wild virulent form, and canine adenovirus type 1 cause a much more severe disease than the type 2.

This is why, whenever possible, and to limit adverse events, using canine adenovirus type 2 live vaccines is preferable.

Killed canine parvovirus type 2 vaccines

Live vaccines are much more effective than killed vaccines because they better simulate a real infection. They should be preferred over killed vaccines.